|

| As Chair of the AAA Composers' Commissioning Committee, I have been writing articles the AAA Music Commissions through the decades. A short history of the Committee is online.

|

Dr. Robert Young McMahan |

| This is the second of a continuing series of articles by Dr. McMahan discussing the history and musical qualities of the commissioned works by the AAA Composers Commissioning Committee, which became active in 1957 under the determined leadership of Elsie M. Bennett. Sources include correspondence and photographs from Bennett's personal archive, articles from various newspapers, journals, and accordion magazines, interviews between McMahan and Bennett, and McMahan's own musical observations of the compositions. The first of the series appeared in the 1997 proceedings, generically entitled Souvenir Journal and Program, published by the AAA for its annual Festival and Competition, held every July, and received by all AAA members. Since then McMahan has contributed one article per year to the Journal (excepting 2008 and 2020), discussing one or more commissioned works, following the chronological order in which they were commissioned. |

The First AAA Commission:

|

| Robert Young McMahan |

| The inspiration for selecting the first commissionee of the newly formed Composers Commissioning committee came, interestingly, from the chairperson, Elsie Bennett's then eighteen-year-old son Ronald, who played oboe in the American Composers Youth Orchestra. At the time, the ensemble was rehearsing Paul Creston's Invocation and Dance (Op. 53, 1954) for an upcoming concert. The young oboist was so enthralled by the New York-born composer's work that he skipped lunch for a week in order to save up enough money to purchase a recording of it. Creston attended the performance and Ms. Bennett, also present (at her son's urging), approached him to discuss a possible AAA commission. They made an appointment for the next week at which he agreed to write an accordion solo. |

| During that time, the composer was completing his twenty-third year as organist at St. Malachy’s Church, in New York, as well as serving as president of the National Association for American Composers and Conductors, and could list among his numerous works five symphonies (of the final six he was to eventually compose), the first two violin concerti, a Requiem and Missa Solemnis, a marimba concertino as well as several works for saxophone (both instruments certainly constituting an encouraging sign for one seeking a composer to write for yet another considerably new and under-represented instrument!), and numerous band and orchestra pieces with such festive generic names as Invocation and Dance (mentioned above), Celebration Overture, and Dance Overture. |

| Although composers of Creston's considerably conservative, tonal, “neoclassical” leanings were going out of vogue in contemporary music circles during the late 1950s, in favor of post-World War II atonal and avant garde figures (such as Ernst Krenek and Lukas Foss, who were to eventually accept AAA commissions as well), his music had nonetheless been highly acclaimed and widely performed, particularly in the 1930s and 1940s, and in Europe in particular. Furthermore, he had been a recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and the prestigious New York Music Critics' Circle Award. All discussion of trends aside, however, Creston's writing was extremely individualistic, highly skilled and inventive, and to most concertgoers, very enjoyable as compared to that of many other more fashionable composers of the day. |

Ms. Bennett found this son of a poor Italian-born house painter (the actual family

surname is Guttoveggio) to be a cordial, patient, and most delightful human

being, who was not only willing to write for the accordion, but confessed that

|

| Creston’s Italian roots and youthful experience as a theatre organist may also

have helped bring about his favorable view of the accordion. With this first commission and all others that were to follow with a host of composers both famous and less known, Bennett supplied important information on the layout and capabilities of the accordion as well as helpful accordion scores and recordings. In addition she would illustrate the accordion’s qualities by playing for the composer and assigning one of the prominent accordion artists of the time to work with him or her as well. In the case of this commission, Carmen Carrozza was called into service, as he would be for a number of future commissions, many for which he gave the official premiere as well. |

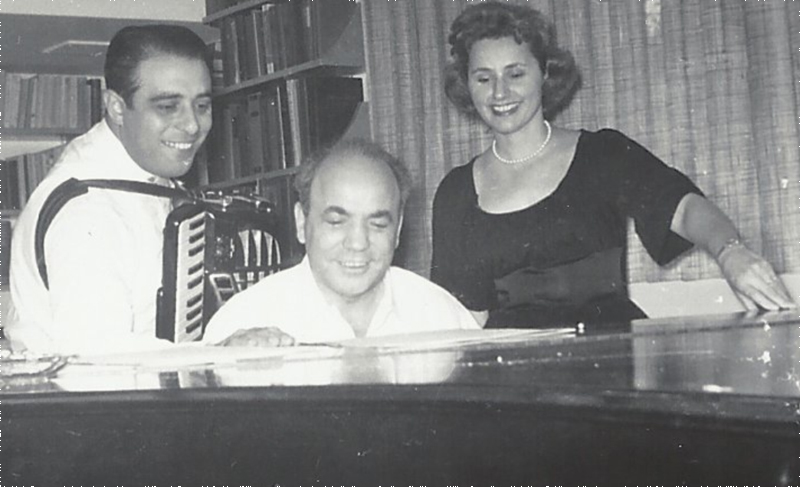

| Carmen Carrozza, Paul Creston, and Elsie Bennett examining the manuscript of the Prelude and Dance. Bennett home and Bennett School of Music, Empire Blvd., Brooklyn New York, October 2, 1957. Bennett AAA commissioned composers personal photo album (unpublished). |

| The Bennett and Creston families soon became close friends, even after the

latter moved in 1968 to the other end of the country following Paul’s acceptance

of a teaching position at Central Washington State College, in Ellensburg,

Washington. The resulting first and historic AAA commissioned composition was given a rather typical Creston title, Prelude and Dance (also the name of a piece for band, Op. 76, written two years later) which he classified as his 69th acknowledged opus. It is a characteristically Crestonian ebullient, melodic, pantonal work, with a dramatic, declamatory, toccata-like opening prelude, imbued with moderately dissonant polychords. For example, the powerful opening, bellows-shaking harmony is an enharmonically spelled C sharp major triad superimposed over a D-diminished seventh chord in the bass [Ex. 1, second measure; note also other similarly overt dissonant tertian harmonic structures in measures 5 and 6]). |

| Example 1. |

| A calmer, rich, dark, searching melody in the bassoon register (Ex. 2) intervenes between the splashy opening and another similar outburst before a dizzy, swirling run plunges into the somewhat jazzy, almost drunken dance in D major and 9/8 time (Ex.3), dominated at first by the Lydian mode (a favorite scale of Creston, which in this instance is built upon a D major scale with a raised fourth note, G sharp in place of the usual G natural). |

| Example 2. |

| Example 3. |

| Except for a rather "pretty” middle section in the violin register (Ex. 4), the heavily accented Dance drives itself incessantly to a climatically wild and joyous end. |

| Example 4. |

| This piece is definitely a “light classic," with its merry-go-round quality and abstract, metrically off-beat, punctuated left-hand oom-pah-pah or single-note accompanimental patterns (typical interplays with melody in Creston’s works in general) in the Dance. But it is also classic Creston at his best, and does not stint in its virtuosic challenges to the advanced performer. He clearly got inside the instrument--the Sano corporation gave him an accordion and Elsie Bennett taught him how to play it--and he turned out a thoroughly idiomatic product which simply would not transcribe satisfactorily to any other keyboard instrument. |

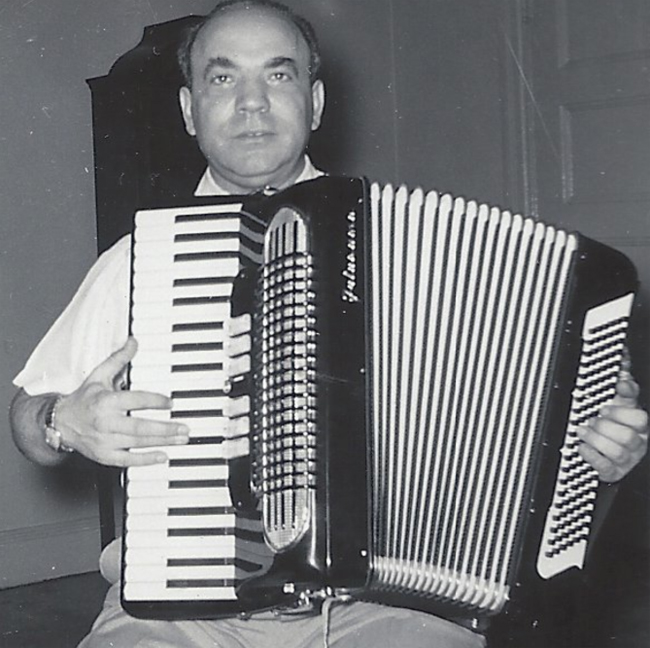

| Paul Creston with “lender” accordion from the Sano

Corporation. July 1957. Bennett AAA commissioned Composers personal photo album |

| The Prelude and Dance was contracted on March 10, 1957 and published by Pietro Deiro Music the following year. It was premiered at Carnegie Hall on May 18, 1958, as part of a large joint concert featuring Andy Arcari, Carmen Carrozza, Tony Dannon, Daniel Desiderio, Angelo Di Pippo, Carl Eimer, Myron Floren, Anthony Galla-Rini, and Charles Magnante. An article by Charles Ross Parmenter in the New York Times the next day does not state which of these major artists played the work in question, though the writer was informed by Elsie Bennett that it was Carmen Carrozza. This is not surprising since Carrozza also coached many AAA commissioned composers and premiered their works over the next decade. |

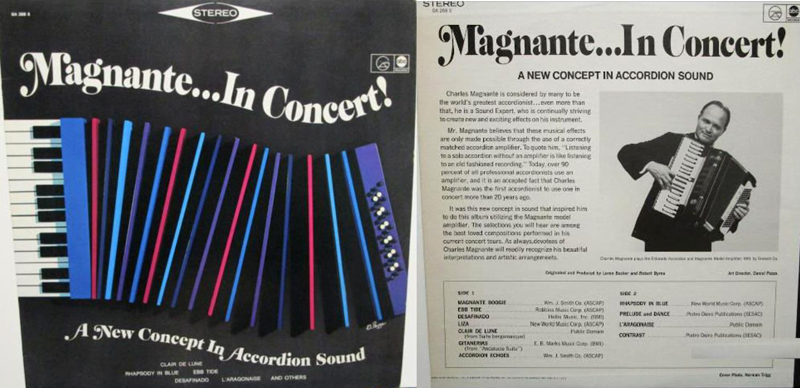

| Also mentioned in the Times is the fact that the Prelude and Dance was to serve as the test piece for the 1958 AAA National Competition. In addition, it was one of the few AAA commissions to enjoy inclusion in a widely distributed commercial LP recording, in this case by Charles Magnante (who normally avoided twentieth century classical works in his repertoire), on the Grand Award label, “Magnante . . In Concert!” (G.A. 268 S). It is probably the most widely liked and performed of all the AAA commissions to date. |

Charles Magnante and Paul Creston discussing the Prelude and Dance. Elsie Bennett home and studio, April 1957; Elsie Bennett photo album. The fact that Magnante frequently played the work in his workshops and concerts is somewhat ironic since Bennett once told the writer that Magnante was among those voting against creating the Composers Commissioning Committee when it was proposed to the AAA governing board. The Prelude and Dance is the only AAA commissioned work Magnante was known to have performed. |

| The Grand Award/ABC Magnante recording, likely produced between 1959 and 1961, including the artist's performance of the Prelude and Dance (the composer's name only appears on the disc itself). The jacket notes indicate that the album was inspired by a new system of accordion amplification developed and promoted by Magnante and, of course, employed in the recording. |

| Creston wrote three more works for the AAA between 1958 and 1968 (to be discussed in future installments of this series), including the all-important Concerto, which is one of the major contributions to the accordion classical repertoire. |