Music Commissions Home | Music Commissions Brief History | Music Commissions Articles List | Composer's Guide to the Piano Accordion

We return once again, as we have in the previous two articles of this series, to the productive year of 1962, in which Elsie Bennett was able to commission four world famous composers, David Diamond (Sonatina), George Kleinsinger (Prelude and Sarabande), Ernst Krenek (Toccata), and Robert Russell Bennett (Quintet for Accordion and String Quartet ["Psychiatry"]). The first two of these were discussed in the 2005 and 2006 issues of the Journal. Now we turn to the third commissioned composer of that period, Ernst Krenek (1900-92).

Krenek was born with the twentieth century in Austria and fell only nine years short of seeing the next. He is one of the most prolific, varied, and respected composers of our time. Though of Czech ancestry (original name: Křenek), he preferred that his name be pronounced as that of a German, dropping the diacritic mark on the "r". Like the similarly long-lived Igor Stravinsky (who died at 89 rather than Krenek' s 91), his music went through several significant style changes.

Not surprisingly, Krenek's earliest acknowledged works are in a post romantic idiom (as were those of Stravinsky and Schönberg), probably due in part to his first noted teacher, Franz Schreker, and the fact that the bloom of the late nineteenth century had not yet begun to significantly fade during his youth. He soon came under the influence of Schönberg's atonality only to abruptly abandon it when he visited Paris and was enthralled by the more conservative neoclassicism of Stravinsky and members of Les six, especially Poulenc and Milhaud.

The European preoccupation with jazz was no doubt also partly responsible for Krenek's opera Jonny spielt auf (Johnny Strikes Up, 1926), which was his greatest success in terms of number of performances and box office receipts. This flamboyant, sassy theatre piece was so popular that during the Third Reich, Hitler suppressed it (due mainly to its biracial theme). However, this did not prevent continued wide sales in Austria throughout the war of a brand of cigarettes named after it ("Jonny"). Krenek next oddly relapsed into a neo-Romantic style similar to the music of Franz Schubert (the song cycle Reisebuch aus den österreichischen Alpen serves as a noted example), before just as abruptly adapting Schönberg's twelve-tone technique before the decade of the 1920s came to an end. The opera Karl V (1931-33), which uses serialization throughout, is a famous example.

Krenek's new leaning towards atonality was probably due to his befriending Schönberg's two great disciples Alban Berg and Anton Webern around this time. Though he was not afraid to vary his style in the ensuing decades, he became one of the noted masters of atonality and serial technique of the twentieth century. Even in his fifties and sixties, he was striking out in new directions of music, trying his hand at electronic and aleatoric modes while still maintaining a persistent level of highly organized serial technique in other works.

Like Stravinsky, Schönberg, Bartok, and Hindemith, Krenek found himself in dangerous circumstances under the siege of Hitler's regime and decided to come to America in the late 1930s. He became a US citizen in 1945. After living in different locations where he taught at a number of colleges, he settled, like so many refugee composers from Hitler's Europe, in the Los Angeles area with his third wife, composer Gladys Nordenstrom in 1950. It would be twelve years before his path would converge with the AAA and the accordion.

The work Krenek was to eventually compose and entitle "Toccata" was commissioned by Elsie Bennett in a letter to Krenek dated April 4, 1962. He accepted the offer and mailed the signed contract to her on April 30. They met to discuss further plans nine days later in New York at the New School where the composer was conducting a rehearsal for the premiere performance of his Quaestio Temporis. According to the composer's final manuscript copy (in the Bennett archive), Toccata was completed that December at his home in Tulunga, California (near Los Angeles). The couple eventually moved to Palm Springs, where Krenek would write his second accordion piece in the 1970s for another organization (to be discussed below).

Two years later Toccata was published in New York by O. Pagani (now owned by Busso Music and still available for purchase), then one of the two prominent accordion music publishers in the United States. It constitutes the first atonal work in the CCC collection and was greatly welcomed by those accordionists who knew of Krenek's importance to the contemporary music scene and the prestige it would bring to the contemporary classical accordion.

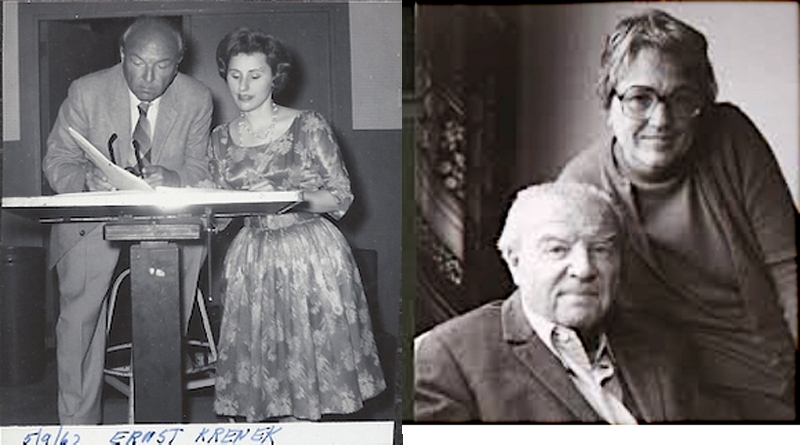

Left: Ernst Krenek and Elsie Bennett at the New School, in New York, May 9, 1962. Elsie Bennett Photo Album. |

Curiously, Toccata was never given any known or documented AAA official world debut, unlike most of its CCC commissioned predecessors, which were usually premiered by Carmen Carrozza in New York and often even received brief reviews in the New York Times or Herald Tribune. It is known, however, that a year after its publication the winner of the 1965 Confederation Internationale des Accordionistes World Competition, Beverly Roberts (now Beverly Roberts Curnow and member of the AAA Governing Board), gave a reading of it in an AAA-sponsored workshop, with Virgil Thomson as lecturer, at the Statler Hilton Hotel, in New York, on September 12, 1965. Her great mentor, Carmen Carrozza, also participated, performing AAA commissioned works by Virgil Thomson and Paul Pisk.

Virgil Thomson, Carmen Carrozza, Beverly Roberts, and Elsie Bennett,AAA Workshop, Statler Hilton Hotel, New York, September 12, 1965 |

Whether or not Toccata was first unveiled at this event, I do know for certain at which performance Krenek, himself, first heard his piece: my own! During the 1966-67 term at the Peabody Conservatory of Music, in Baltimore, Krenek held a chair as visiting professor of composition. I was in my third undergraduate year there as a composition student of Stefans Grové and, like many other fellow students, was eager to play something by the composer at the weekly composition seminars, which Krenek attended. At some point during during the spring semester, I was permitted to perform Toccata for the gathering. My colleagues, most of whom were skeptical of the notion that the accordion could ever play any kind of "serious" music successfully, were astounded at what this piece proved the instrument could do. One particularly strong "disbeliever" experienced a sudden epiphany, exclaiming that it was in his opinion the best of all the Krenek works he had heard that year. (To this day it has the same effect on hardline accordion skeptics, especially composers and professional musicians, for whom I have played it).

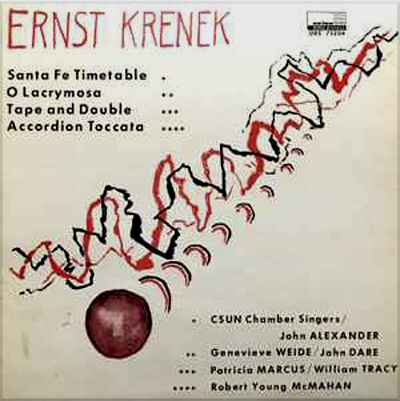

Krenek was pleased as well, stating that it had turned out even better than he had expected. It was then that I realized he had never heard Toccata performed, even though it was already five years old and had been in print since 1964. I was very grateful to have found this out after I had performed it for the maestro rather than before! Decades later I was happily surprised to find a mention of this seminar and my performance in a letter from Krenek to Elsie Bennett dated December 23 (though he could not recollect my name at the time). I was further gratified when, before the end of the school year, Krenek asked me to record the work for him in the Peabody studio. Eight years later, in 1975, he included the recording on an Orion LP of his works.*

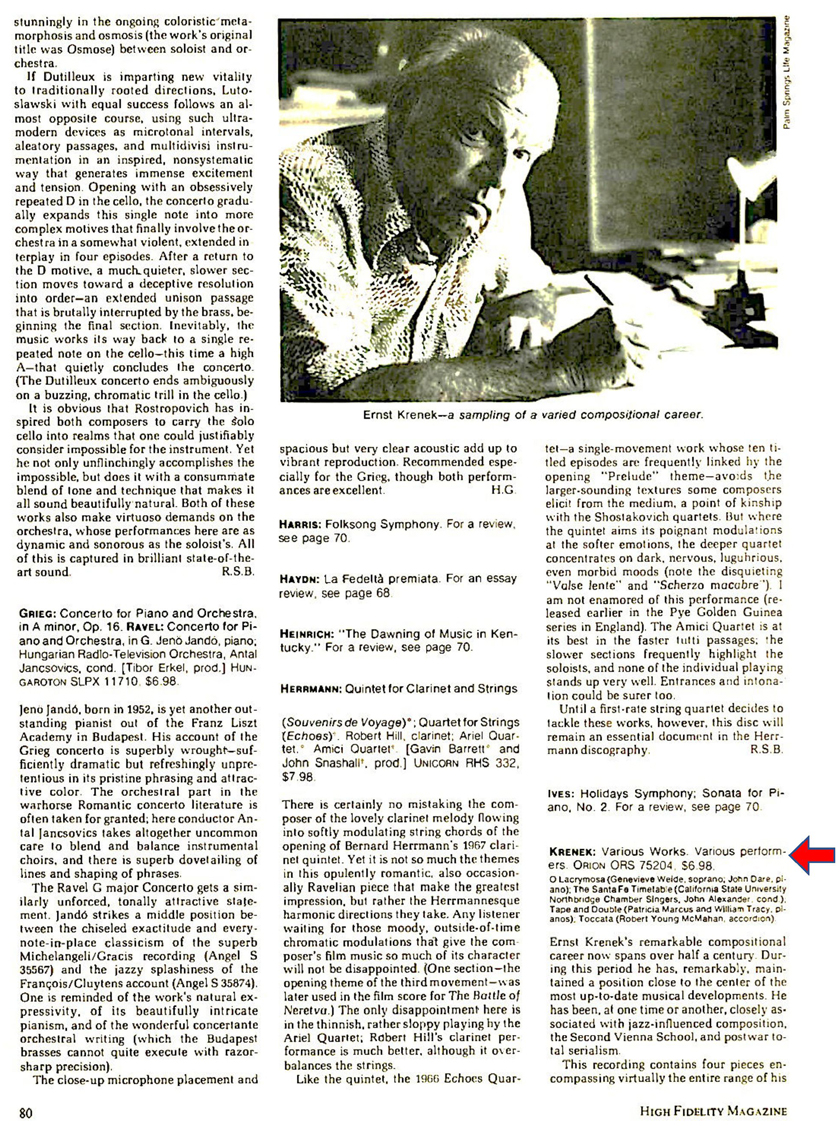

The recording received good reviews in popular recording magazines of the time including High Fidelity (June 1976)** and Tempo (September 1977). Because the Toccata was part of a collection of recorded works by one of the most renowned and still thriving composers of the twentieth century, it may have been, and may yet still be, the only AAA commissioned work to be so widely exposed to, as well as critiqued by, the general classical contemporary music world due to its exposure in these widely read periodicals.

Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, where Krenek first heard a performance of his Toccata for accordion |

Record albums of works by lesser-known composers are far less likely to attract critical published attention with such wide distribution.

|

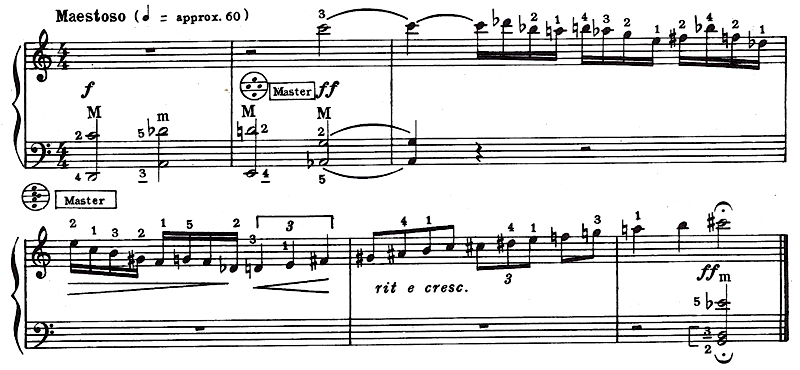

The Toccata is divided into four movements that are played without pause: Andante, Allegro moderato, Adagio, and Allegro. Following the Allegro, there is a brief Maestoso coda reminiscent of the declamatory opening of the first movement. The title is a generic one derived from the Baroque era. It was most commonly applied to keyboard works, particularly the organ, and was usually very bombastic and virtuosic, though it could consist of several sections of different tempi and moods.

Krenek possibly chose the title because of the comparison often made between the accordion and the organ, and, except for the modern atonal leanings of the work, it certainly is of the nature and free form of its seventeenth- and eighteenth-century predecessors.

At Bennett's request, Krenek supplied the following description of the piece in a letter to her dated January 22, 1963, that was published in part a year later in Accordion Horizons ("Holiday Issue," 1964):

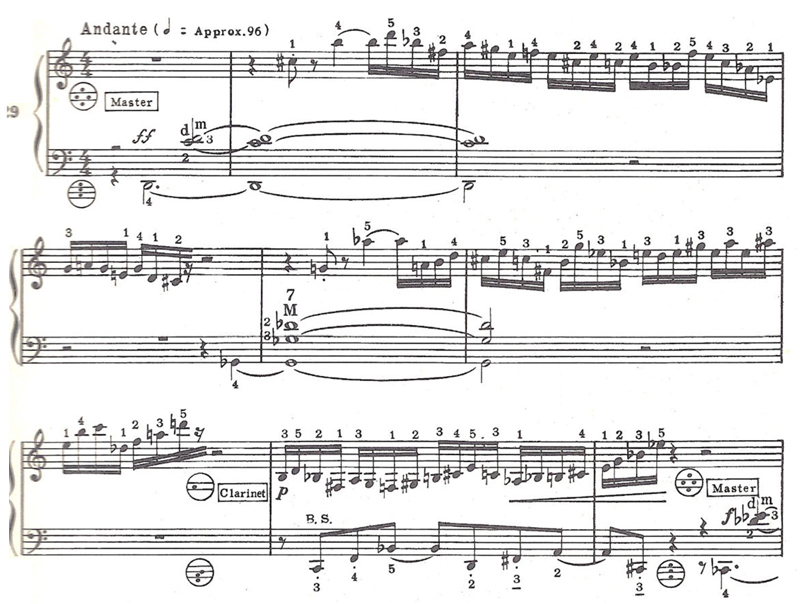

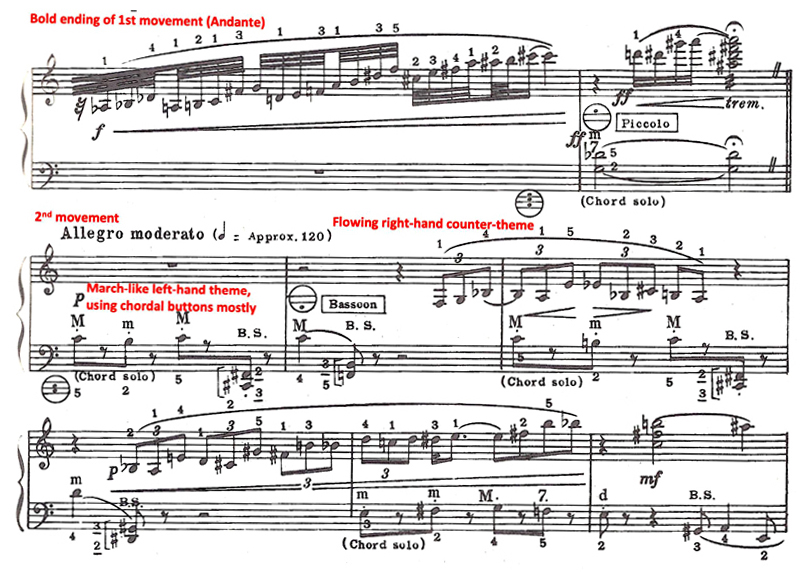

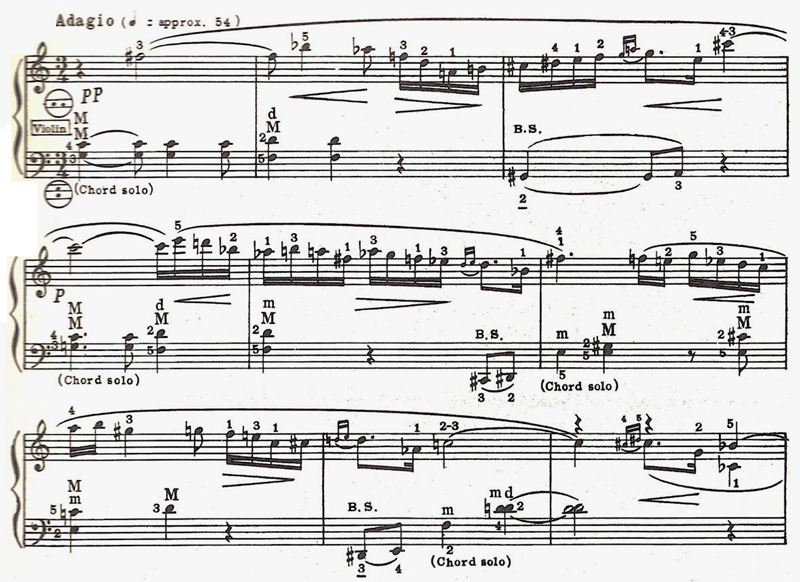

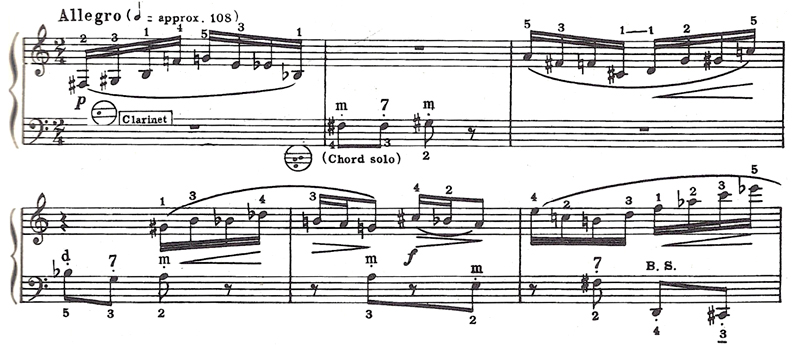

| The piece consists of four sections to be played continuously. A forceful prelude with massive chords and vigorous runs, alternating with quiet passages (as in parentheses) [see Example 1], is followed by a somewhat march-like section [the Allegro moderato], setting off a melodic line in various tone colors against a chordal staccato accompaniment. [See Example 2] The third section [Adagio] is lyrical in character. It rises from gentle, mysteriously floating sounds to a powerful climax. [See example 3] The last section [Allegro] is a brief scherzo, making special use of the rapid changes of chords possible on the accordion. [See Example 4] The piece concludes with the massive sounds of the opening [the Maestoso coda]. [See Example 5] |

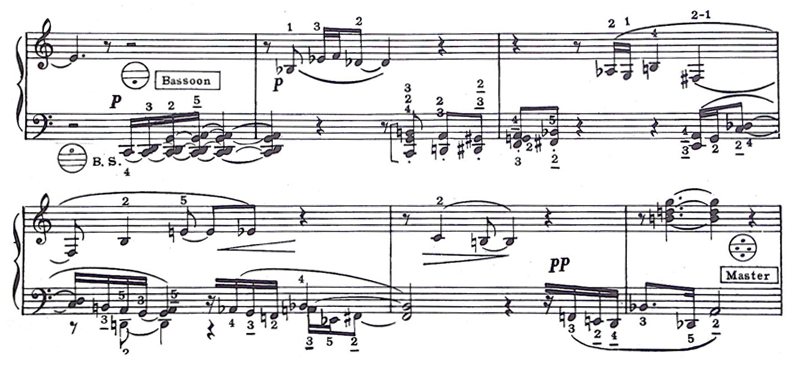

| Example 1. Opening of the first movement of Toccata. |

| Example 2. Dramatic end of first movement (Andante) and double-themed beginning of march-like second movement, Allegro moderato. |

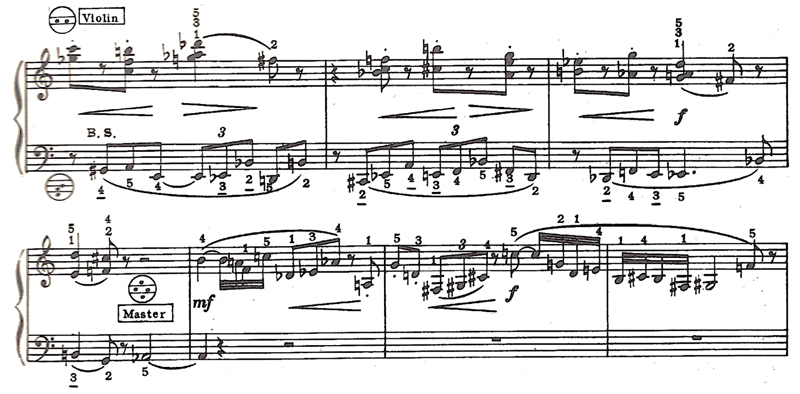

| Example 3. Beginning of second movement (Adagio). Expressive, violinistic melody, using the gently bright sounding "violin" stop, with largely polychordal left-hand accompaniment created by combinations of chordal buttons in the stradella system employing the high, transparent sounding "alto" register switch. |

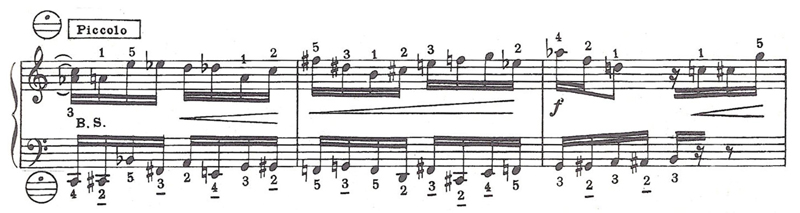

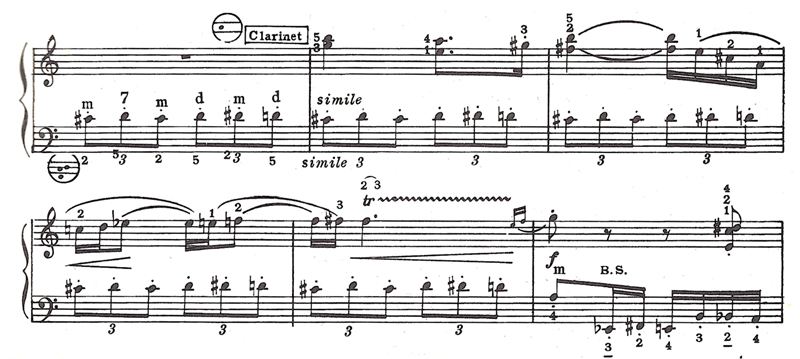

| Example 4. Beginning of fourth and final movement (Allegro), initially using the smooth, somewhat muted sounding right-hand "clarinet" register vs. the deeper sounding, subdued "soft bass" register in the staccato left-hand accompaniment. |

| Example 5. Dramatic Coda (Maestoso), reminiscent of the first movement's declamatory opening, with full register stops employed at near maximum accordion volume. |

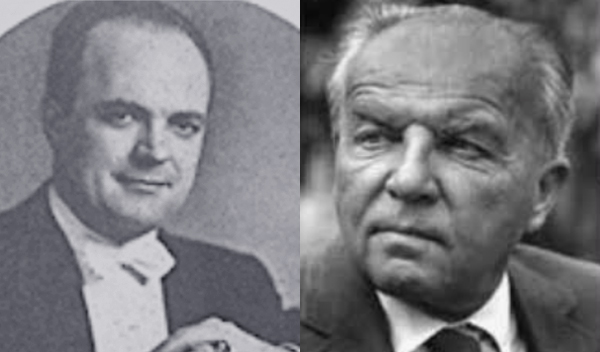

From the beginning to the end of Toccata, it is unmistakably clear that Krenek had made a thorough study of the instrument. As was Bennett's custom with all the commissioned composers, she sent Krenek various scores of previous AAA works for him to pour over and assigned a professional accordionist to assist him as an advisor and experimenter. In this instance, her choice for the consultant was Oakley Yale (1916-90), who lived on the other side of Los Angeles from the composer, in Inglewood, where he and his accordionist wife Melba ran the Yale Accordion Academy.

Oakley Yale; and Ernst Krenek around the time of his composing Toccata |

From all his exploration of the instrument Krenek goes on in his above letter to Bennett to express his observations of the accordion's stradella left-hand system and the effects of the instrument's various register switches, almost all of which he employed in his score:

| Comments: [I will use] no specifically new devices, such as twelve-tone or serial techniques, mainly because of the limitation of the left hand to a few chordal patterns. But these very limitations suggest harmonic combinations of which one would not easily think without being driven to them. This makes the accordion interesting to a composer who does not wish to stick to the conventions of tonality. On the other hand, if he does not want to produce so-called "polytonality," he must resist the temptation of simply piling chords of different keys on top of each other, which is another challenge. Finally, the various octave doublings in the several registers of the instrument offer interesting possibilities for distributing depth and perspective throughout the design. I enjoyed all these aspects, especially since I had not been aware of them before becoming a little better acquainted with the accordion. |

Having said that he would not use any "twelve tone or serial techniques," Krenek did employ certain basic atonal, non-serial musical language throughout the greater part of Toccata, only occasionally taking certain liberties. This generally means he avoided melodies based on outright seven-tone traditional scale and modal sources, melodic passages using traditional tonal scale runs and chordal arpeggios, constant tertian harmonic structures as they would relate to one another functionally in a consistently applied major or minor key, traditional harmonic progressions, and allowing any pitch of the twelve-tone chromatic scale to recur, except in direct succession, in a melodic line or harmonic structure until at least ca. six other different pitches have been employed beforehand. A good example of such anti-tonal style writing may be observed in the first eleven notes of the first measure of Example 2, in which all the notes of the chromatic scale are used except E-flat, and are arranged in a way that does not suggest any established tertian harmonies or major or minor scale passages: Ab, Bb, Db, A, B, C, F#, G, D, E, F. Note also that nowhere else in the right-hand part of the excerpt is there any suggestion of traditional tonal harmonies or scale fragments. These traits permeate all the movements of the composition.

Therefore, Toccata is mostly what is referred to as a "freely atonal" work rather than a "twelve-tone serial" one in which the composition would be exclusively derived from a strict order of all twelve tones of the chromatic scale, called a "set." Whether the technical process of composing an atonal work has been highly strict and organized (serialized) or not (non-serialized), the end result will sound essentially the same to the listener if the above-described general non-tonal processes have been applied.

Regarding Krenek's remarks about the left-hand stradella format's limitations but nonetheless interesting challenges for the atonal composer, the free-bass left-hand system, with its four or so octaves of chromatically ordered single notes in the left-hand manual, so often used for the highly contrapuntal contemporary works from the 1970s onward, was, in the view of many accordionists, a considerable improvement over the stradella system. However, it was not then played by most of the established artists in America until around the mid-1960s. In fact, only a few advanced students in the country had taken it up at that point. Thus, Krenek was given guidance in the stradella format only, as was true of all the AAA composers before him and quite a few afterwards.

Having pointed out all of the above, however, virtually no accordionist of any stripe did and still does not play the stradella system, and it is likely to remain a permanent part of the accordion's anatomy for ages to come. This may at least partly explain why the majority of classical accordionists play instruments that have both left-hand systems either side-by-side or transformable to each other via a mechanical switch in the left-hand sector. This double-system arrangement will continue to make the accordion an exceptionally facile and versatile instrument for all types of music in perpetuity. ***

Returning to the issue of atonal music procedures and the limitations of the stradella system, the latter has often been berated for its having merely one octave of single notes (actually only a major 7th range, one pitch short of the upper octave pitch), which can only be somewhat clumsily extended up or down an octave or two via register switches, and its prefixed chordal buttons of major, minor, major-minor 7th, and diminished chords, all in their circle-of-fifths arrangement. This format therefore seems to suggest that the accordion is limited to tonal music in major and minor keys and tertian harmony, and not suited to modern developments in classical music that escaped such bonds in the twentieth century. Therefore, being introduced only to that format at the time Krenek was commissioned by the AAA, proved to be an obvious challenge to him, long an atonal composer by then and thus having no great use for such mechanically pre-set tonal music patterns.

Composers such as Krenek are particularly strict about any pitch being heard in any octave other than the one in which they write it in a given melodic passage. Therefore, the fundamental and counterbass rows of the120-bass system pose a particularly problematical melodic challenge to a strict 12-tone atonal composer. That said, Krenek was as freely chromatic and atonal in the left-hand part as he was in that of the right-hand, despite octave displacements that can result from a melody whose range exceeds a major 7th in range in the stradella system (hence one of the primary reasons for the creation of wider ranged free-bass systems in the first place). Nonetheless, to avoid such unwanted melodic irregularities, Krenek fastidiously limited all his left-hand single-note passages in the Toccata to the range of C to B, as can be observed in the left-hand single-note melodic lines in all the musical examples in this article.

In keeping all his so called "bass solo" lines to this C-to-B range, Krenek was obeying the official gamut established and recommended to accordion manufacturers by the AAA decades ago and that Oakley Yale doubtlessly instructed him to employ. Ironically, though, accordion manufacturers do not always adhere to this standardizing command, sometimes fixing the range as far below C as F#! Therefore, depending upon the accordion brand and model at hand, the purity of Krenek's left-hand melodic passages may be beset by octave displacements after all, regardless of his effort to prevent such.

Despite these left-hand range frustrations presented by the stradella system's single-note rows, the damage seems insignificant, however, in Toccata since Krenek's single-line melodic left-hand segments are often immediately offset by consequent passages of equal or greater length making imaginative use of the chordal buttons, be they successive separate ones that are somewhat melodic in effect or are combined to create interesting polychords. Regarding the former, see how effectively Krenek uses the chordal buttons to form the initial theme of the second movement before it is joined by the strongly contrasted right-hand one when it enters approximately two measures later (Example 2).

Another observation to make here is that though Krenek is breaking the rules of atonality by using traditional tertian triads in the left-hand part, they are considerably abstracted because they are not derived from a singularly shared diatonic key as one triad progresses to the next. For example, measures 1 through 3 of the second movement (Example 2) contain alternations between C-major and B-minor bass chord triads. This will not seem to be in the key of C major since it contains no B-minor triad among its seven diatonic harmonies and the key of B-minor contains no C-major triad in any of its three scale types (natural, harmonic, and melodic). The chordal succession of E-minor, F#-minor, G-major, F-major-minor 7, and E-diminished in measures 4 and 5 of the same movement also frustrate the impression that they belong to any single key throughout. Krenek also makes extensive use of this tonally non-committed device in the fourth movement, but more in the role of a non-thematic rhythmic accompanimental figure driving the main themes in the right hand (to be discussed below; see Example 9).

Returning to melodic range observations in the stradella system, there are places in Toccata, as with many other stradella-only contemporary accordion works, where accordionists who have instruments containing both free bass and stradella left-hand systems may switch from stradella to free bass for greater range and pitch accuracy (as they appear in the printed score) as well as sonorous purity of pitch (should the melodic range be greater than a major 7th, , though Krenek does not allow that to happen in Toccata, as already mentioned) and then back again to stradella, where the score allows enough time to make the switch changes. Places in Toccata where this would be possible are measures 17-22 in the opening Andante movement (Example 6); measures 6-8, and 23-26 (Example 7; easier than measures 6-8) in the Allegro moderato (second) movement; and measures 31-33 (Example 8) of the final "scherzo" Allegro movement.

Examples 6, 7, 8 (below). Examples of left-hand melodic passages for the stradella system that allow enough time for the left hand to easily switch to the free bass manual to play them and then quickly return to the stradella system when it is once again needed. (Note: the fingerings shown are for the stradella system and would have to be changed for the chromatic free bass format, but not necessarily for the quint one). |

| Example 6. First movement (Andante), measures 17-22. Note that the right-hand Bassoon register will cause the music to sound an octave lower than written while the left-hand "Soprano" switch will render its part three octaves higher than written. Therefore, the performer will need to locate the proper octave and/or octave-changing left-hand register switch in which to play the latter in the chosen free bass manual. |

| Example 7. Second movement (Allegro moderato), measures 23-29. The chosen stradella left-hand register indicates that the line will be perceived to be heard as written. Therefore, of the three choices of registers offered by either of the prevalent free bass systems - as written, as written coupled with an upper octave, or octave higher than written alone - the choice would be either the first or the second of these options, but definitely not the third. |

| Example 8. Fourth movement (Allegro), measures 31-33. As in Example 6, the registral switches in this excerpt will cause both manuals' notes to sound in different octaves than are written. In this passage the actual sounds will be one octave higher in the treble clef and three octaves higher in the bass clef. Therefore, the two lines combined into one staff would actually sound as follows: |

| The necessary choice of the three registers listed in Example 6 would then have to be that of sounding an octave higher than written while playing in the middle-C range of either of the free bass formats. |

Despite the limitation of the stradella left-hand system's melodic range to a single octave and discussions above alluding to the multi-octave emancipation from that shackle by the free bass systems, Krenek and many other noted composers before and after him have delighted in a number of imaginative things that can be done with the old 120-bass offerings, especially regarding the fixed-chord buttons. Some of these uses have already been touched on where they occur in Toccata, but more deserves now to be added - and admired - below.

Particularly effective are the many occurrences of polychords, which can so easily be produced in the left hand stradella manual literally at the touch of two to four chordal buttons simultaneously. (As accordionists reading this know, it is normally too difficult and often impossible to employ the thumb in the left-hand button manual, so only the four fingers are commonly used).

Left-hand polychords are especially noticeable throughout the first movement, where crashing left-hand dissonances are created against lengthy, declamatory, falling and then rising sixteenth-note right-hand passages. For example, in the first measure, a deep single-note D is sounded and sustained through a two-button polychord consisting of C-diminished and D-minor. Thus, three fingers have easily produced a dissonant simultaneity of six separate pitches (C, D, E-flat, F, G-flat, A). A similar, though more dissonant, left-hand formation follows in the consequent phrase of this opening period in measures 4 through 6, the result of combining the G-flat-major and D-flat major-minor seventh chord buttons (Gb Bb Db F Ab Cb, a piling up of 3rds amounting to a Gb11 chord). See Example 1 above.

Regarding the Adagio (third) movement's left-hand, a lovely, luminous effect results from similar two-button left-hand polychords in the middle/high "tenor" register, which serve as accompaniment to the very expressive, languishing right-hand lines heard therein. See Example 3 above.

It is therefore easy to see how almost all twelve tones of the chromatic scale could be produced at once by only using four chord buttons, though Krenek never avails himself of that potentially excessive opportunity in this piece, to which he alludes in the second of his two quoted statements above.

In other places, Krenek gives a more melodic role to the chordal buttons. This is especially true in the second movement, where two principal themes coexist between the two manuals: a stiff, militant, mostly staccato one, in regular eighth-note/eighth rest values, initially in the left hand, and played almost exclusively on single chord buttons (discussed earlier above); and a flowing line (which is more properly the main theme) dominated by eighth-note triplets, starting in the right hand, with phrases overlapping the left-hand units in uneven lengths. The two elements make for a very clever, well-crafted counterpoint, colored by the high, meshed sound of the melodically used staccato left-hand chord buttons. The two principal ideas are frequently exchanged between the manuals, returning between other materials in somewhat disguised form later to form a subtle rondo-like form. See Example 2 above.

In the closing "scherzo" movement, as Krenek refers to it, the initial quippy, brief, right-hand phrases, formed mostly of a variety of non-tonal or non-tertian four-note sets in sixteenth notes, sound antiphonally with equally short-lived left-hand responses consisting of single-chord buttons which use all four available stradella chord qualities in a variety of chromatic successions (such as F-sharp minor to F-sharp major to G-sharp minor in the second measure). These often add up to eight or nine different pitches of the twelve-tone gamut and come across more as rapid blurs of chromatic color than separate tertian structures. See Example 4 above.

This activity eventually gives way to more legato right-hand phrases that are accompanied in hemiola fashion by lengthy left-hand ostinato figures cast in rapid staccato eighth-note triplets and, again, using alternating chord buttons of all four qualities. Such full chords, so agilely executed at this tempo (quarter note equals 108, as marked in the score), could not be successfully duplicated in one hand on the piano or free-bass accordion without sounding clumsy or weighted down. See Example 9 below.

| Example 9: Fourth movement (Allegro), measures 13-18. Example of rapid moving chordal ostinato accompaniment in stradella chordal buttons to right-hand melodic theme. |

Perhaps as important as any of the above discussed idiomatic accordion traits of the right- or left-hand manuals Krenek exploited in Toccata is his excellent and insightful use of timbral color via the registral shifts available in both manuals of the accordion. Oakley Yale was probably of important assistance here in that he doubtlessly demonstrated these sounds for the composer. Krenek's choices of stops throughout the Toccata could not have been more perfect and were indispensable to its beauty and musical effectiveness. The reader is encouraged at this point to revisit all the musical examples in this article to study the many changes of registral switches in both the right- and left-hand manuals that Krenek so carefully and intuitively chose to highlight his greatly varied and expressive melodies, harmonies, and polyphonic textures. Such a wide kaleidoscope of timbral color are part and parcel of most effective atonal works and are given a high value and priority in the masterpieces of that genre.

The bombastic opening of the first movement is appropriately set for the full master shift in the right-hand manual, thus opening all its ranks of reeds under full pressure from the bellows for maximum forte strength. But before the movement is over, Krenek has employed the mellow, muted sound of the "Clarinet" stop, the dark, rich "Bassoon" register, the somewhat raspy, but delicate effect of "Oboe," and the bright, piercing "Piccolo" choice. Similar changes in octaves, timber, and aural weight take place in the frequent left-hand changing of switches, too. About as many such right- and left-manual registral changes are employed in the remaining movements as well.

Particularly striking are the beginning of the Allegro moderato, whose right-hand theme begins with the unexpected dark sound of the "Bassoon" register; the beautiful timbral contrasts between the various long, expressive right-hand lines of the Adagio, due to the employment of the bright "Violin" switch in one passage, and the rich sound of "Bassoon" in another, with all of these supported by a lovely, translucent, high left-hand register; and the almost whispering use of the "Clarinet" stop at the outset of the Allegro, offset at the end of the movement by the electronic-, sine-tone-like effect of the highest, single-reed switches ("Piccolo" in the right hand and the "Soprano" switch in the left) of both manuals propelling a rising sixteenth-note rush into the stratosphere in deliciously dissonant two-part counterpoint (the last illustrated in Example 8 above).

In sum, Krenek's Toccata is one of the finest examples of highly imaginative and colorful use of accordion registration in the literature, and accounts for a major part of the work's (and the instrument's) success. Furthermore, the composition as a whole is a testament to one of the twentieth century's most resourceful, creative, and amazingly eclectic composers who, though perpetually in demand with endless commissions, found the time to promptly write this miniature masterpiece for the accordion (and another over a decade later; see below). It deserves a place in every classical accordionist's repertoire and can serve as an excellent introduction to atonal music for artists who are new to contemporary music. ****

In 1976 Krenek wrote yet another solo for accordion, as just mentioned above, entitled Acco-Music, commissioned this time by the Accordion Teachers Guild (ATG). I felt honored that he asked me to be his advisor/editor for this work which was carried out via many letters back and forth between us. For this occasion, we did discuss the chromatic free bass system and its possible employment in the new piece. The result was a 3-staff score wherein the performer could choose either the free bass or the stradella system, or exercise the option to go back and forth between the left-hand formats according to taste. Many of the AAA commissions since that time have followed the same plan.

Acco-Music was published the next year by Ars Nova and further edited by California accordionist Donald Balestrieri. Both it and Toccata are presently available through Ernest Deffner Music (Busso Music). Joseph Macerollo recorded it several years later (LP; Interaccordionista; Melbourne SMLP 4034); a recent CD recording by Alfred Melichar is also available on the Extraplatte label, LC 8202; EX 252 095-2); and an online recording may be heard at https://soundcloud.com/ensemble-wiener-collage/ernst-krenek-acco-music-f-r

Following the work on Acco-Music I urged Krenek to write yet a third piece which would be a chamber work for accordion with one or more "standard," non-accordion instruments. He was interested in the proposition but being extremely busy with a long list of commissions ahead of him, this unfortunately never came to be.

Notes:

* Orion ORS 75204. The album is entitled Santa Fe Timetable (the title of another Krenek work on the recording) and may be heard streaming online in the Naxos Music Library.

**The full review, by Robert P. Morgan, in High Fidelity (June 1966, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 80-81) is attached below.

*** For readers unfamiliar with the left-hand systems of the accordion (as well as any other aspects of the instrument), see my Composer's Guide to the Piano Accordion, a free download on the AAA website, <"https://www.ameraccord.com/commissions/ComposersGuide.pdf">https://www.ameraccord.com/commissions/ComposersGuide.pdf

In July 2007, Dr. McMahan performed Toccata as well as another AAA commissioned work, Prelude and Caprice (1972), by Joel Brickman, and a new work of his own for accordion entitled Magic Box, at the eleventh annual Master Class and Concert series at the Tenri Institute in New York.

For a more detailed account and analysis of Toccata, see Dr. McMahan's article "Idiomatic use of the Accordion in Atonal Music: A Study of Toccata by Ernst Krenek, and a Work by the Writer," in the UK journal Musical Performance (2001; Vol. 3, Parts 2-4, pp. 45-68). The entire issue was dedicated to the accordion in all its facets.

For the 2008 Master Class and Concert Series at Tenri Institute, Dr. McMahan performed two AAA commissioned works, Robert Baksa's Sonata for accordion and an abridged version of Henry Cowell's Concerto Brevis, by William Schimmel, with Dr. Schimmel playing the orchestral part on piano. McMahan also premiered his Three Songs on Academic Poems by Walt Whitman, for soprano and accordion, with Suzanne Hickman, soprano, and again at the American Accordion Musicological Society Festival, Radisson Hotel, Valley Forge, PA, March 7, 2009, where he was the recipient of the "honoree of the year" award.

Robert P. Morgan review of Krenek's 1966 LP including Toccata. High Fidelity, June 1966 issue

The AAA Composers' Commissioning Committee welcomes donations from all those who love the classical accordion and wish to see its modern original concert repertoire continue to grow. The American Accordionists' Association is a 501(c)(3) corporation. All contributions are tax deductible to the extent of the law. They can easily be made by visiting the AAA Store at https://www.ameraccord.com/cart.aspx which allows you to both make your donation and receive your tax deductible receipt on the spot.

For additional information, please contact Dr. McMahan at grillmyr@gmail.com

2026 AAA 88th Anniversary Festival Daily ReportsAugust 13-16, 2026 Latest NewsAn Accordion Extravaganza! exciting concert, April 26th, NY. 2026 AAA Elsie M. Bennett Composition Competition 2025 AAA Elsie M. Bennett Composition Competition Results AAA History ArticlesHistorical Articles about the AAA by AAA Historian Joan Grauman Morse Music CommissionsHistorical and analytical articles by Robert Young McMahan. Recent articles:

AAA NewslettersLatest newsletters are now online. |