Music Commissions Home | Music Commissions Brief History | Music Commissions Articles List | Composer's Guide to the Piano Accordion

With the total number of AAA commissioned works standing presently at over sixty, the subject of this article is at approximately the halfway mark of the many composers and their contributions to the accordion world that have been discussed in chronological order of their commissions since this series began in the 1997 edition of the annual AAA Festival Journal. It also marks the beginning of the commissioning of a considerable number of composers from the "Baby Boomer" generation (commonly defined as a member of the generation born between the end of World War II and the mid-1960s) and, in a few cases, beyond, all of whom, happily, are still alive at the time of this writing.

The first such commission took place in 1972, when most of the "Boomers" were completing their college degrees and beginning their professional lives. The composer was Joel Ira Brickman, who was born in 1946 and was indeed in the early stage of his professional career, teaching some composition at his soon-to-be alma mater, the Manhattan School of Music, where he earned his Master's degree in Composition, and soon thereafter at the now no longer extant Marymount College in Tarrytown, New York, and then, for many years to follow, instrumental music in various elementary, junior or middle, and senior high schools in northern New Jersey.

Other Boomer composers, including the writer, were to follow Brickman since then: Roger Davidson, José Halac, Dave Soldier, Timothy Thompson, and accordionist/composers John Franceschina, Karen Fremar, Will Holshouser, Guy Klucevsek, Joseph Natoli, William Schimmel, and myself, all conservatory- or university-trained professional composers.

On April 11, 1972, AAA Composers Commissioning Committee Chair and founder Elsie Bennett sent a letter of commission to Brickman, assigning a solo to be completed "hopefully" by June 1. Despite this very short allotment of time, Brickman managed to produce a seven-and-a-half-minute virtuosic piece he entitled "Prelude and Caprice." Also moving almost as quickly, Bennett promptly submitted the work to the congress of the Confederation International des Accordeonistes (CIA), which met in Caracas, Venezuela, for consideration to serve as the test piece at the1973 Coupe Mondiale, to take place in Vichy, France, in September of that year. The congress approved the selection, and copies, published by Pietro Deiro Publications, were sent to all contestants.

A second distinction for this 29-year-old composer's first and only accordion piece was that he made two arrangements of it, one for standard stradella bass and the other for the increasingly popular free bass. This was the first of a number of AAA commissions to accommodate the two left-hand systems.

The composer was to later comment in a press release he wrote for Elsie Bennett, that he enjoyed writing for the instrument and was impressed by its unique features and special effects:

| I am greatly impressed with the accordion's ability to provide polytonal and polychordal sonorities [probably referring to the stradella left-hand chordal buttons]. Its many registration stops also provide superbly effective contrasts. I hope to have done the instrument its due justice in my usage of several of its functions. I believe that other composers of my generation should investigate the overlooked virtues of the accordion. I am grateful for this opportunity. |

Indeed, he was grateful, as a brief note of thanks dated just a few days after he submitted his manuscript to Bennett can attest:

| I am sending to you this belated note to express my sincere appreciation for my recent commission. I had great pleasure and gained a most valuable education in its composition. It is very benevolent of you to take interest in my music and, in turn, to encourage my writing for the accordion. Here's contemplating more music for same in the future. |

As had been true of many other composers Bennett commissioned, Brickman dedicated his piece to her.

Brickman also gave Bennett both brief and more detailed descriptions of his piece in a couple of undated memos intended for press release:

| The first page of the Prelude exposes all the material to be used throughout. It runs in free development containing many lyrical themes that are later to be developed and exposed in the Caprice. The Caprice is very quick and gay, as opposed to the slow, brooding quality of the Prelude. |

To this, Bennett added "Mr. Brickman’s work is definitively a virtuoso piece; but not conceived simply for that reason. It makes an energetic exploration of the expansive possibilities available with the accordion."

In the second memo, Brickman went into more detail:

| My Prelude and Caprice endeavors to afford a solo accordionist with an opportunity to interpret two highly contrasting moods within a comparatively short duration. It opens with a forcible cadenza-like passage built upon a short tone row. [See Figure 1 below.] The row then takes varied shapes. It is segmented, inverted, juxtaposed, etc. The resultant moods created with it also vary greatly. At times the initial idea is abandoned allowing for related lyrical themes to offset the Prelude’s intensity. After the essential statements subside, another cadenza-like section, utilizing the right hand solely, extends into the contradictory Caprice. This is in the fashion of a scherzo, but designed in a free-rondo form. It makes much use of disguised material from the Prelude; but instead of the original pomposity, here is a surge of gaiety and choreography. The coda is a culmination of as many previously announced themes as possible. The primary theme in the Prelude is noticeably elaborated. The overall texture of the Prelude and Caprice is in a freely chromatic and extended harmonic stylization. |

The "short row" Brickman refers to is not suggestive of the strict 12-tone serial technique ala Arnold Schönberg but is rather a kind of melodic motif that will undergo the permutations to which he refers (segmentation, inversion, etc.), only slightly reflecting some of the serial techniques of composition used in, but by no means limited to, the atonal school.

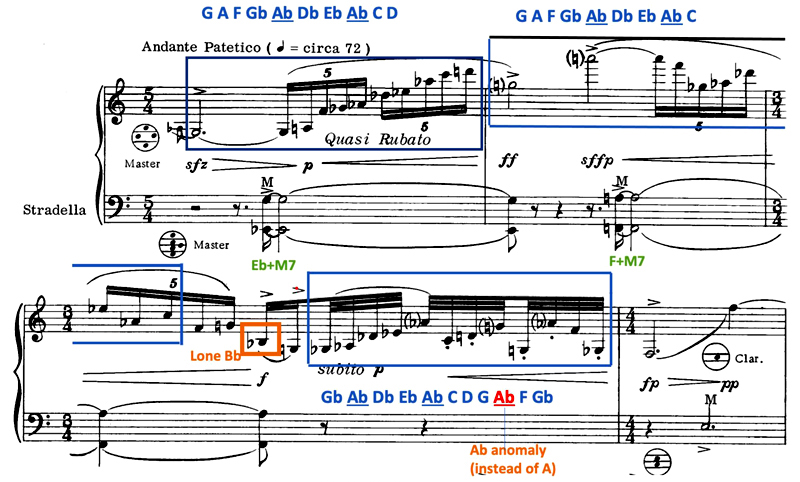

The set, as it were, appears to be only the ten notes (excepting the initial anomaly of the grace note A-flat that precedes the set) in the right-hand part of the Prelude's first measure, employing this melodic order: G, A, F, G-flat, A-flat, D-flat, E-flat, A-flat, C, D. The fact that the A-flat occurs twice and there are only nine different pitches of the twelve-tone gamut represented (B, B-flat, and E are the missing members, though the B will be heard in the left-hand G major chord in the first measure, but only there) also refutes the possibility of thinking of the passage as a presentation of a classic atonal serial row, in which no single pitch class is allowed to recur before the next employment of the set, and where there are normally all twelve different pitches of the chromatic scale forming the set.

View Figure 1 to see how the composer forms the opening proclamatory passage with the full set and then continues the line breaking it into different sized segments and octave displacements. One of the three "missing" notes of the set, B-flat, makes a single appearance in measure 3. The A-flat recurs enough times to be heard as a kind of spoke in the wheel of notes, as if to be a stabilizing factor, though it does not actually take on the power of an anchoring tonic pitch as would the first note of a major or minor scale that serves as the melodic and harmonic anchor in tonal music.

Forming a stabilizing floor to these virtuosic right-hand runs are two sustained, rather film noir-like-chords (augmented triad with major 7th, symbolized as "M+7" in Figure 1) in the left hand by means of combining ready-made major chordal buttons with single-note ones employing fundamental or counterbass buttons. The first, beginning in measure 1, forms E-flat M+7 (Eb G B D), and the second, beginning at the end of beat 3, measure 2, a transposition of the same chord quality a major 2nd higher, FM+7 (F A C# E).

Figure 1. Prelude, measures 1-4 |

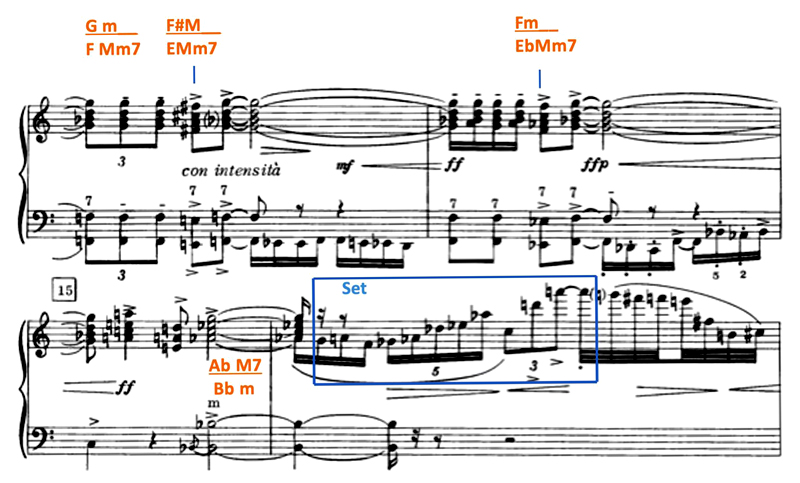

Brickman also makes wide use of the polychords he mentioned in his admiration of the accordion’s unique features quoted above, pitting standard stradella bass fixed major, minor, major-minor seventh, and diminished chord buttons against contrasting and sometimes conflicting standard chords in the right-hand keyboard, thus allowing varying levels of consonance and dissonance to occur. See Figure 2 for one example of the more obvious occurrences of such harmonic superimpositions.

Figure 2. Prelude, measures 13-16. Superimposed tertian harmonies and a recurrence of the set. |

Quartal harmonies occur in the left-hand accompaniment of one section (measures 72-90) of the Caprice to offer contrast to the prevalence of tertian structures, superimposed or not, elsewhere in the work (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Caprice, measures 86-89. Rustic sounding quartal harmony accompaniment to right-hand melody |

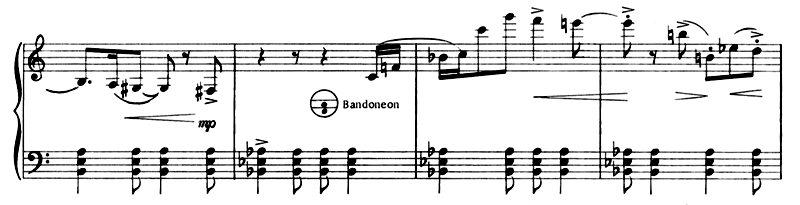

Other textural contrasts to this often busy, largely contrapuntal work may be found in the Prelude, measures 24 through 33, where a brief left-hand melodic passage played only on the minor chord row turns into a serene A minor-B minor ostinato accompaniment to a somewhat frenetic right-hand melody; and, in the Caprice, a comical right-hand melody is accompanied by brash oom-pah, or reversed "pah-oom" left hand figures for six bars, starting at measure 98. See Figures 4a and b.

a. Prelude, measures 23-25. Left-hand ostinato accompaniment on minor chord buttons. |

b. Caprice, measures 98-100. Strutting oom-pah and "pah-oom" left-hand accompaniment. |

Figure 4. Special left-hand accompanimental figures in the Prelude and Caprice. |

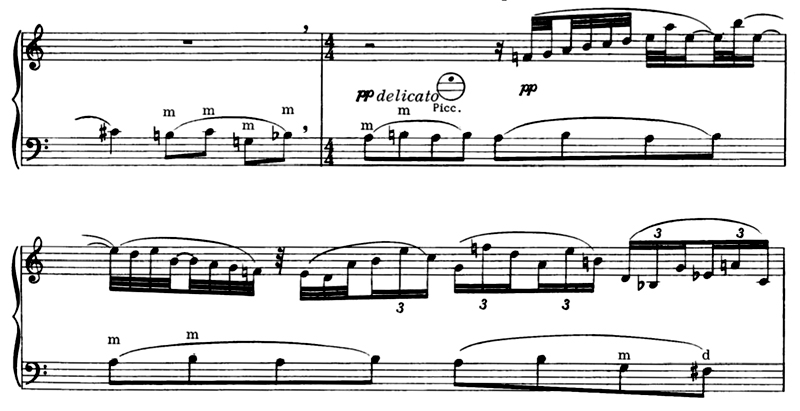

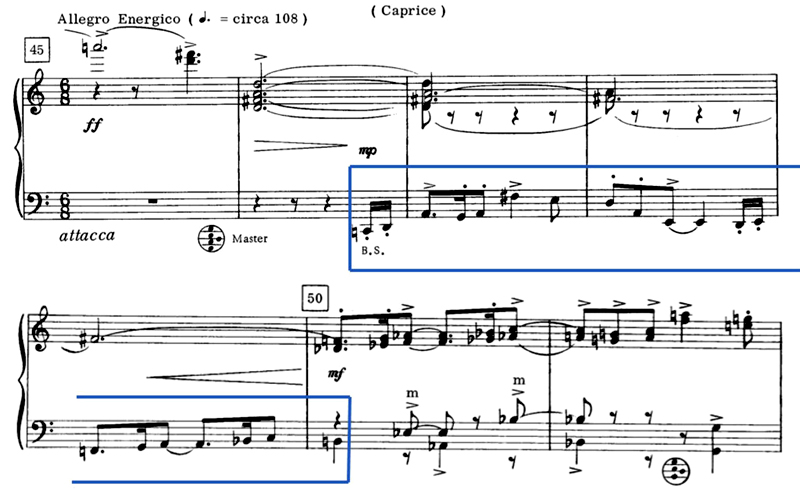

Though the composer describes the Caprice as being "in the fashion of a scherzo," its main motto, first heard in the bass (see Figure 5) is in a lilting and largely consistent meter of 6/8 (with an occasional disruption of meter change), suggesting more the nature of the popular Baroque gigue dance form employed in so many works of that period. There are, however, moments of hemiola when the compound duple nature of the gigue shifts to the rhythmic equivalent of 3/4 time, possibly evoking another Baroque dance form, the courante. While these notions may be debated, the rest of Brickman's description of the movement, that it is "designed in a free-rondo form", is beyond argument, with clearly recognizable returns of the opening motto four times (at measures 63, 119, 129, and 142), though always varied somewhat rhythmically and/or intervalically each time.

Figure 5. Beginning of the Caprice, measures 45-51, and main recurring motto (in blue box). |

Sandwiched in between these flexible reincarnations of the motto are delightful contrasting sections that do, as the composer states, sometimes take departures from the main motivic elements of the work. Two of these were sampled in Figures 3 and 4b above.

As can be easily observed from the above displayed excerpts alone, the Prelude and Caprice is a considerably complex, highly chromatic, and often "dissonant" work whose easily definable though largely disjunct melodic lines, complicated rhythm, and complex harmonic formations render it treacherously difficult for the keyboard musician. To do it justice, the performer must possess the utmost level of technique and insightful musicality, expressivity, and experience in modern music. For all these reasons, it may well be one of the most technically and expressively difficult test pieces ever required for the formidable AAA National Championship Competition and the Coupe Mondiale mentioned above.

There is no formal documentation of how or when Brickman and Bennett first met, but I had suspected that an earlier commissioned composer and one of Brickman’s composition mentors at the Manhattan School of Music, Nicholas Flagello, may have recommended him to her.* However, in 2018 I was able to locate and contact Brickman, then living in Paramus, New Jersey, who informed me that, though Flagello had recommended his young student for a position to teach composition extension courses in the Manhattan School of Music and that another prominent faculty member, also one of Brickman's composition teachers, Ludmila Ulehla, additionally recommended him for a position at Marymount, where he taught various music courses as well as clarinet and oboe for a few years (his principal instrument was oboe), neither mentor had anything to do with the commission. This was also true of another illustrious AAA commissioned composer with whom Brickman had studied during his undergraduate years at MSM, David Diamond. Flagello did mention his AAA commission once to Brickman, however, unlike Diamond, who never did so regarding his three accordion contributions to the AAA.**

Instead, the offer of a commission to Brickman was the result of a near unbelievable coincidence. While vacationing in the Catskills region at the popular Hotel Brickman (no relationship to the composer) in scenic South Fallsburg, New York, he met by sheer chance Elsie Bennett, also lodging there. In their conversations he was excited to hear that she was to be joined shortly by Paul Creston, a composer Brickman greatly admired, and was thrilled when Bennett invited him to stay and meet him upon his arrival. During this time Bennett must have been convinced enough by the young composer’s credentials to offer him a commission virtually on the spot. This was highly unusual for Bennett, who usually pursued composers of fame or those of considerable note that she knew well and whose music she had heard before then doggedly convincing them to write for the accordion. She must therefore have seen something special in this young man that prompted her to take such a "gamble."

Old postcard view of Hotel Brickman, South Fallsburg, New York, where Joel Brickman and Elsie Bennet first met. An Ashram now occupies the property. |

It was probably quite clear to Bennett that Brickman’s career was taking off quite auspiciously at that time on several fronts. This included a highly positive review in the New York Times by the renowned critic Raymond Ericson of a January 14, 1972 concert at the Manhattan School of Music of Brickman’s master’s degree thesis, a half-hour-length work for orchestra, soprano, and piano set to a poem by Muriel Rukeyser entitled "A Thousand Nights." It also won a composition contest in the school. These successes along with the AAA commission and its ultimate acceptance as the test piece for both the 1973 AAA National Championship Competition and the international 1973 Coupe Mondiale, not to mention the conferring of a Master’s degree from the prestigious Manhattan School of Music, certainly rendered 1972 a momentous year in this burgeoning composer’s life, and bade well for his future.

In his 70s as of this writing, with a full and varied career of teaching behind him, Brickman continues to compose and is particularly proud of a number of his works that have been performed in New Jersey over the years, including a concert overture, Prelude and Dithyramb, premiered by the Ridgewood Symphony Orchestra, John Lochner, conductor; Suite, for woodwind ensemble; and settings for voice and orchestra of poems by E. E. Cummings, performed by the Ridgewood Chamber Orchestra, Walter Engel, conductor.

There is no record of a formal premiere of the Prelude and Caprice. This is possibly because so many contestants who enrolled in the AAA National Championship competition and/or the Coupe Mondiale performed it so soon after the piece’s publication due to its being the required test piece. In addition, other contestants may have voluntarily chosen to play it in the open Senior or Virtuoso Original Composition divisions of the AAA competitions.

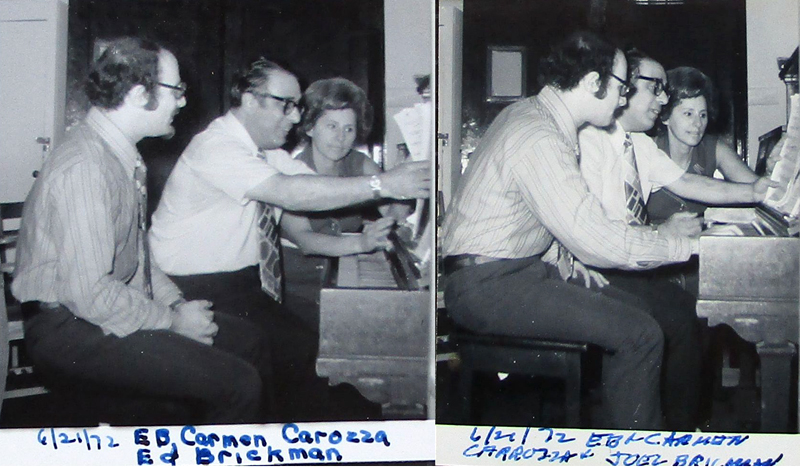

Another unusual, but less significant, situation regarding the christening of this new commission was, given what a “shutterbug” Bennett was affectionately known to be among her friends, there are only two photos including Brickman appearing in her large photo album collection of commissioned composers. Dated June 21, 1972, they both include Brickman (in profile only), Carmen Carrozza, and herself seated at the Bennett living room piano in Brooklyn going over the score.

Though serving as an accordion consultant to Brickman, Carrozza never played the piece himself in any of his public performances. Nevertheless, it is probable that a number of other classical accordionists have since included it in their programs over the years. Offhand, the writer knows of two for sure: former AAA President, Mary Tokarski and himself. It deserves many more hearings performed by many others.

Joel Brickman, Carmen Carrozza, and Elsie Bennett discussing a draft of the Prelude and Caprice, June 21, 1972. Bennett home. The only known Bennett-generated photos of the composer. Elsie Bennett photo album. |

* Flagello composed his Introduction and Scherzo for the AAA in 1964, eight years before Brickman’s piece. It was the twenty-third AAA commission at that point. See my article on Flagello and this piece in the 2011 installation of this series.

** Two solos, Introduction and Dance and Sonatina; and Night Music, for accordion and string quartet. See the articles including Diamond and these works in the 2004, 2005, and 2015 installations of this series.

Hear a recording of Prelude and Caprice via the link accompanying its listing on the AAA Music Commissions home page at ameraccord.com/aaacommissions.php

Dr. McMahan performed one of the AAA commissioned works, Prelude and Sarabande (1963), by George Kleinsinger, at the 2018 AAA Master Class and Concert Series. He also premiered two new works there, his own Three Tweets, for clarinet, accordion, and piano (2018), and Objects Viewed in a New Light, (2018), for accordion solo, by Daniel Galow, a recent graduate at The College of New Jersey, where he studied composition with Prof. McMahan.

The AAA Composers' Commissioning Committee welcomes donations from all those who love the classical accordion and wish to see its modern original concert repertoire continue to grow. The American Accordionists' Association is a 501(c)(3) corporation. All contributions are tax deductible to the extent of the law. They can easily be made by visiting the AAA Store at https://www.ameraccord.com/cart.aspx which allows you to both make your donation and receive your tax deductible receipt on the spot.

For additional information, please contact Dr. McMahan at grillmyr@gmail.com

2026 AAA 88th Anniversary Festival Daily ReportsAugust 13-16, 2026 Latest NewsMario Tacca, Mary Mancini AAA fundraiser. 2026 AAA Elsie M. Bennett Composition Competition 2025 AAA Elsie M. Bennett Composition Competition Results AAA History ArticlesHistorical Articles about the AAA by AAA Historian Joan Grauman Morse Music CommissionsHistorical and analytical articles by Robert Young McMahan. Recent articles:

AAA NewslettersLatest newsletters are now online. |